Who powered the passage of the charter school amendment in Georgia? African-Americans who have been chronically denied good public schools….

By Douglas A. Blackmon

One of the most striking results of the vote on Amendment 1, which was approved by Georgia voters on Tuesday and creates an independent commission to authorize public charter schools in the state, is the absolutely extraordinary level of support received from African-American voters.

In the 20 Georgia counties where African-Americans make up half or more of the population, the amendment was approved by 61% of all voters and in 14 of those 20 counties. (In two of the other six counties, the amendment still got 49% of the vote; in the other four, support ranged from 42-44%). In the 13 counties where more than half of Georgia’s three million black citizens live, the margin of support was even higher: 62% approval.

The bottom line: Georgia’s black counties overwhelmingly desire dramatic new alternatives to the conventional school systems that have failed them for more than a century.

That level of support flatly contradicts one of the flimsiest canards used to criticize Amendment 1—and charter schools in general. That is: the idea that somehow charter schools end up hurting minority or poorer students while disproportionately helping white and middle class children. The actual performance of charter schools in Georgia has always defied such claims. African-American students and all children living in urban areas with failed conventional public schools, like Atlanta, have benefited far more from charters than any other groups.

That reality of the vote is even more remarkable when plotted across a map of Georgia. Amendment 1 was overwhelming approved in populous areas like Atlanta, Savannah and Macon—where a new generation of residents from all social and ethnic backgrounds want an eclectic, diverse, “city” life but where the archaic system of local school board control of public education has been a sustained failure for decades. The amendment also received huge support in places like Cherokee County, where the local school board in recent years has been perhaps the most hostile to all charter schools—and any kind of meaningful school reform—of any location in Georgia. The monopoly so long held by chronically failing institutions like those is what Amendment 1 will now challenge.

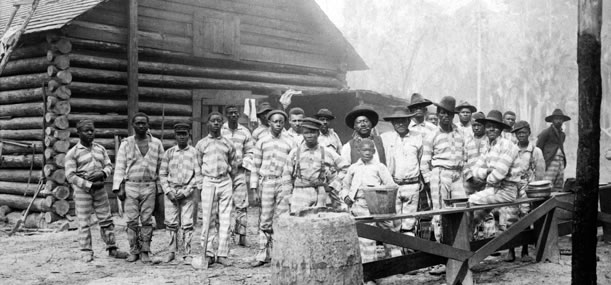

The support of Amendment 1 among African-Americans is also notable against the backdrop of the Georgia Supreme Court decision in May 2011 that struck down as unconstitutional a previous version of the state charter commission. That ruling on a lawsuit organized by school boards that oppose all charter schools led directly to the campaign for Amendment 1. In the 2011 ruling, the Supreme Court ignored some substantive issues around state funding that in truth needed judicial scrutiny, and instead struck down the old commission using a cruelly naïve logic that would have been comical if it had not been so nauseatingly ironic. The court reached all the way back to Georgia’s defunct constitution of 1877–a white supremacist document passed expressly to end the brief period of true citizenship enjoyed by formerly enslaved African-Americans after the Civil War–and cited as the basis of their ruling against the charter school commission the very constitutional article that first mandated racially segregated schools in Georgia.

How richly appropriate then, that African-American voters in Georgia used the ballot box to renounce the state Supreme Court’s absurdist logic. A total of more than 805,000 “yes” votes (out of a total of 2.1 million statewide in favor of the amendment) were cast in the counties with the largest number of black voters. That includes DeKalb (54% African-American), where the amendment passed with 64% of the vote; and Fulton (43% African-American), where it was approved by 66%.

And where did Amendment 1 get the absolute highest level of support: in 66% black Clayton County, the poster child for abominable school boards, where the system lost its accreditation as a result of staggering dereliction by the elected board. African-American families in Clayton have been in open revolt—ousting some school officials at the polls, moving to nearby jurisdictions with better schools and mounting immense pressure for improvements.

Voters in Clayton gave the charter school amendment a stunning 71% approval. That says it all.

This doesn’t have anything to do with this topic, but I dream of being a writer when I grow up, was it hard to publish your book?

This is such a great way to base your vote on the issue of Charter schools in Georgia! I fully agree with you!

Doug, I had the pleasure of hearing you speak today at the LRAN conference closing plenary. Coincidentally, a friend pointed out to me that it’s also Juneteenth, which casts an even more somber light on the discussion of what you termed “neo-slavery”. Thanks for your work.

I work for a teachers’ union, so naturally, this web-post caught my eye. On the issue of African-American support for charter schools, you’re right. In Georgia, and in many areas, there is popular support for charter schools. But popular support for charter schools isn’t a sign that charter schools are necessarily succeeding while their public counterparts fail. The slick and well-funded marketing campaign behind the corporate education reform movement, which has created two widely screened feature length films to lionize charter schools and celebrate reckless trigger laws while demonizing unionized public school teachers, is very much targeted at communities of color. Moreover, after decades of systematically under-funded public schools, it’s logical that any parents would be eager for an alternative.

Charter schools can be judged by their merits on a case basis. Yet for every story of charter school success, there are numerous stories of failure and fraud. Moreover, the larger reform movement itself is doing a disservice to those rare charter schools that legitimately strive for academic excellence, fiscal responsibility, and positive labor relations by treating the charter model itself as, to use your term, a panacea for all manner of challenges facing students in our system of education.

Albert Shanker, former president of the AFT, was an early proponent of charter schools, but turned against the movement when he recognized that it would simply become a tool to privatize education. His predictions were right. This post and your earlier comment response seem well-balanced, if a little generous in connecting popular support for charter schools with challenging white supremacy. I hope you look further into this issue. Capitalist or not, you seem like a pretty good egg, and I especially appreciate your fondness for the word “canard”.

Hello Jake,

Thanks for your note. Anyone who sees through it all to discover my inner good egg-ness is good by me. 🙂 I enjoyed the discussion in Washington. That’s an important group, working on the most important question in all of labor and American enterprise.

On charter schools, I completely understand your perspective–and could not more agree with you that the demonization of teachers and teachers unions has been an idiotic, misguided red herring that entirely misses the reality of what should be happening in education and has consumed three decades of energy that should have gone elsewhere. I also don’t agree with anyone who argues that public education in the US, broadly, is in a state of crises or massive decline. The data simply doesn’t show that. Instead, the US is delivering a quality basic education to a larger and more diverse population of its citizens than at any time in its history and with greater success than any ethnically diverse society in human history. So I’m no mad dog anti public school person. I’m the opposite–a pro public school advocate who believes some systems in some places are catastrophically broken and need broad public support and meaningful innovation to restore public schools as the center of that community.

As far as your take on charters, though, I hesitate to assume too much since we haven’t been able to truly discuss this. But based on just you note, I think you assume too much, way too much, about charter schools, and probably haven’t opened yourself to a fair consideration of them. I run into this a lot–and please don’t take it the wrong way–but so many people working hard and valiantly and brilliantly in conventional public schools so often readily accept all the various explanations and special circumstances that ostensibly excuse a conventional public school or system for decades of failure, but then turn around and reject everything but the simplest kind of topline statistical analysis for charter schools. Over and over again I hear denunciations of charter schools based on methods that the person doing the denouncing would be outraged to see applied to conventional public schools. I’m sure you’re right that there have been clever campaigns by charter school advocates through the films you reference and by other means to sway public opinion, and I’ll accept that they loaded the deck in their favor. I don’t actually know if that’s the case, but its human nature. What I do know, however, is that none of that could begin to exceed or match the kind of intellectual dishonesty that I’ve seen used to defend failing conventional schools all my life.

My path has been precisely the opposite of Albert Shanker. I was dead set against the notion of charter schools when they were first beginning to be authorized in Georgia, but then became deeply involved in school reform efforts in Atlanta, and concluded a charter was the only possible way to achieve what we were trying to do. The conventional system was so broken, so entrenched, so under the control of parties who put self preservation far above children’s education, so hostile to change, there was no possible way anymore for it to evolve toward a different place. In the 15 years since then, charter schools have had a tremendously positive effect on public schools in Atlanta. Their growth has been restrained (sometimes to a degree that was in fact illegal) but in recent years by a fairly good process of evaluation by the local central administration and by the state education authorities. Poorly performing charter schools have been shut down rather aggressively–something that has never ever ever ever ever occurred with conventional public schools here (or anywhere if you are honest about it). Charter schools in Atlanta are also not significantly the products of the “for-profit education company” bogeymen that are so often invoked in these conversations. That phenomenon has occurred in other places, based on what I’ve read, but not significantly here. Instead, the great majority of charters in Atlanta were created by a grassroots community organization (in the case of the K-8, 700 student, majority-minority school my wife and I helped found), a large local philanthropic foundation with a large K-8 program and now building a high school that is overwhelmingly African-American, the KIPP program–serving again an overwhelmingly minority population, and then in rapidly descending size another community-based organization that took over a school from a national non-profit school network, and several other schools, none of which have the corporate backing you suggest.

Meanwhile, the existence of charters has kept (or attracted back) a substantial population of middle class and generally aspirational African-American families and a much smaller number of middle class families of other ethnicities who were rapidly exiting public schools or had already done so. Meanwhile, the total number of students in conventional Atlanta public schools has continued to fall dramatically. Over the past 10-20 years, that fall has not been the product of white flight—which had cynically and immorally cut the school system’s population by 40 percent in the 1970s and 1980s. Instead, the continuing abandonment of the public schools has been overwhelmingly by African-Americans who finally grew weary of the suggestion that they were supposed to accept obscenely failing schools. As these charter schools have succeeded, they have in many cases also had the effect of spurring dramatic innovation and improved execution in nearby conventional schools, and have restored for many people in neighborhoods like mine the idea that public education actually is worth considering. As a result, as waiting lists for entry into our charter school have grown longer and longer, our school encouraged parents to seriously consider the traditional school to which our neighborhood is zoned. Now a very meaningful number of families are attending there who would never have even briefly considered doing so before. As the first cohort of students who began their school years in our elementary a decade ago have begun graduating, the “movement” that created the school is now doing tremendous work to improve and build community ties into the traditional public high school serving this part of Atlanta.

Bottom line, no fair assessment of charter schools in Atlanta could in any way suggest that charters have not been just “a” source of good for public education, but in truth probably the “only” source of true reform and progress during a time that the system’s only significant indicators of progress–marginally higher test scores and graduation rates in some areas–turned out to be a vast fraud leading to criminal indictments of the superintendent and dozens of others. (And by the way, if you look at statistical comparisons of student performance at Atlanta charters versus Atlanta conventional public schools, you’ll see that charters consistently outperform. But don’t be fooled by numbers suggesting that in some cases the traditional schools did almost as well as charters–since all of that data was the product of this vast test cheating conspiracy. And even if the data were reliable, that would also be a method of analysis, as I suggested above, that I suspect you would never accept as legitimate to compare the performance of conventional schools or their teaching staffs.)

Based on all of that, I wouldn’t be off base to make a sweeping argument that charter schools—at least ones developed in the manner that they have been in Atlanta—should become the primary weapon of change in improving public education. But I don’t make that argument. Because I believe that charters are just one very potent approach to disrupting and reforming some public school systems–particularly ones like Atlanta that had driven completely off the rails and where every internal reform approach like the ones I think you would suggest as more appropriate have failed completely, utterly and repeatedly. Across the board. Those are simple, empirical facts. At the same time, I don’t support the willy nilly creation of charter schools in areas where the traditional public schools are performing well. I would oppose the broad privatization of public schools by any means (and I don’t see convincing evidence of that happening even now with charters).

What I do see, more clearly than anything else, however, is that there is not one iota of empirical evidence–none whatsoever–that governance of public schools by locally elected boards composed of amateur politicians has, at any time in the past 75 years, led to better, more enlightened or more effective school leadership and progress than any other number of alternative systems of governance. (As much as I hate to say it, I also am hard pressed to find any compelling quantifiable evidence that unionization of school faculties–or obstacles to unionization–(set apart from, say, simply higher compensation) have led to higher performance by students.)

Instead, what is clear is that local control of schools–from middle Georgia to Glenridge NJ–remains in place and ferociously defended by its supporters not for the betterment of education but to enable special interest groups (ethnic ones, local business ones, employee groups, political organizations) to maintain power over who gets a cut of government revenue, who gets prestige, who gets employed, and, sadly, which colors of children can be excluded or minimized. Meanwhile the arguments for alternative forms of organizing schools are at the same time so enormously logical and compelling and worthy of consideration and implementation–statewide administration, regional administration, non-political and purely professional organization, all manner of things almost all of which are almost invariably fought tooth and nail by the same groups that see the still infinitesimal growth of charter schools as a diabolical threat. I hate to hear myself say that. Because I used to believe in local school boards. But then I asked myself why? Other than the fact that they’d always been there, why did I believe they were so important, even after watching thousands of them try to block the integration of public schools and tens of thousands of them unnecessarily consuming vast community resources simply by their unnecessary redundancy from one little spot on the map to the next. And more than anything, watching them most of the time be simply benign, very often ridiculous and far too frequently disastrous.

So I have abandoned my allegiance to that tradition of American life, and having done so it’s now remarkably clear how little basis there ever was–after the frontier days of scratching together the first schools town by town–for that whole structure of education. You should give that some thought too. Also consider the possibility that charter schools are not necessarily what you assume. And if you’re ever in Atlanta, visit the one I’m associated with. Ask the teachers–everyone one of whom is certified and hyper-qualified by every measure and compensated at the highest salary scale of any public teachers in the state of Georgia–what they think.

Would love to talk with you more about this. Anybody who cares about public education is my friend, even if we disagree.

Doug

You’re just wrong.

Public school is not a “failing institution”.

The society at large is not really smart about how to educate poor children of color,

and that lack of expertise isn’t going to go away in charters — they don’t know either.

The black parents who are asking for this are just taking an easy way out.

Figuring out how to educate their children under a new framework is absolutely

guaranteed to be every bit as difficult as reforming the old public framework into

something decent would have been. “The data” have always shown that the two

strongest predictors of success in school have been the father’s income and the

mother’s education level. Switching to charters is not going to change that.

Thanks for the response, George.

But I’m not sure what you’re saying is “wrong” in that posting from several months ago. It’s a simple, irrefutable fact that African-American voters overwhelmingly supported passage of that amendment, out of frustration with the decades of poor performance and neglect from the public schools serving their communities. That’s what that article said, and that is absolutely correct.

It appears what you were really trying to say was that anyone who supports charter schools in any circumstances is wrong. On that, we just disagree. Charter schools are no panacea. There have been extraordinarily successful charter schools–that achieved results traditional schools couldn’t under the same circumstances—and there have been charter schools that were failures. But for African-American students in places like Georgia, traditional public schools have been overwhelmingly failures for a very long time. It’s time for some other options.

Your suggestion that black support for charter schools amounts to something about African-Americans “taking an easy way out,” is a bit obnoxious. First, what would be wrong with taking “an easy way” if it led to public schools that were more successful for more children. Isn’t that what we all are looking for?

But more important, what is one to make of your line about “the data”? It’s incredibly simplistic to assert that essentially the only meaningful variable in whether a child succeeds at school is his or her father’s income and mother’s educational level. There is plenty of other “data” pointing toward other factors. If your interpretation is true, why do anything at all? You seem to be saying that since the parents predetermine the outcomes of the children, any kind of change in education is hopeless.

That’s way too cynical for me, and violates the most basic creed of an educator, that every child can be a successful learner.

That was a rude way to respond to Mr. Douglas Blackmon. A very closed minded response.

I just found this blog today (12/31/12); however, what better way to begin 2013? I think that people MAY be surprised at the number of public school teachers (like myself) who voted FOR Amendment ONE. Just like most other Clayton County voters, some teachers supported the positive systemic changes found in Amendment One. That desire for change went beyond race and ethnicity. It was forged in the very fiber that created this wonderful society of ours. It was directly linked to the fundamental concepts of “…Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” found in the Declaration of Independence. Only more responsive and effective local and state educational systems, along with involved parents, can properly prepare our children for future lifetime success.

HAPPY NEW YEAR Everyone!

Doug’s analysis adds to the expectation that metro Atlanta county voters and African Americans should expect more than token representation on the state appointed board.

I totally agree, Mayor Franklin. The challenge now for charter school supporters and the legislators who put the amendment through is to see that the new commission is implemented in ways that ensure the (I believe exaggerated) concerns of opponents aren’t fulfilled.

Now would also be a good time for Georgia to pay more attention than ever to the State Board of Education. It will have final say over everything the commission decides, and ought to be more closely followed by all.

[…] AJCer Doug Blackmon, who supported Amendment One, tackles the topic of African-American support in a piece you can read here. A taste: That level of support flatly contradicts one of the flimsiest canards used to criticize […]

[…] AJCer Doug Blackmon, who supported Amendment One, tackles the topic of African-American support in a piece you can read here. A taste: That level of support flatly contradicts one of the flimsiest canards used to criticize […]